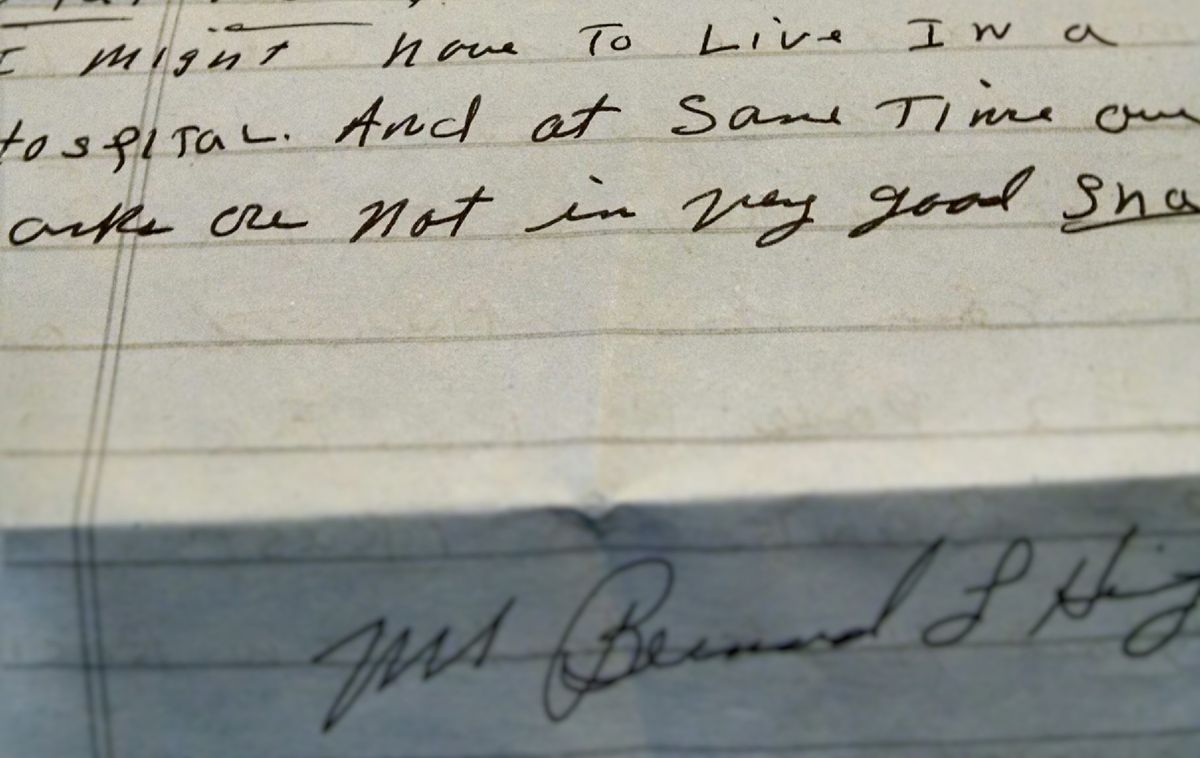

Upon death, ’91 note found: ‘I might have to live in a hospital’

A son reflects on the passing of his father, who suffered from Pick's Disease, and the struggles they faced navigating America's long-term care system for the elderly.

It has been three weeks now since dad has passed.

Mostly, I’m experiencing feelings of relief.

But also, lots of affirmation and vindication. Although I hate the term vindication.

The affirmation has come in the form of an avalanche of condolences. I’ve heard from literally hundreds of people from around the U.S. Some of the most striking sympathies have come from people who I know to be my enemies, or who at least don’t care for me and who made it very effectively known a few months prior to dad’s death.

And they all say the same thing: “Your dad could not have had a more dedicated advocate.”

Of course, I always have known that to be true. And maybe some thought I went a little overboard in being his advocate.

But let me get to the root of why I may have seemed a bit “overboard.” My dad said for many, many years that he was not well. He told people he was sick, that he hurt, had trouble walking. Nobody believed him. Most people disrespected him.

Dad could be mean, and often he was accused of being violent, but never did I see him be physically violent. Verbally abusive? For sure.

Now we know that was all part of the disease. In fact, my dad died a very textbook death from Pick’s Disease (behavioral-variant frontotemporal degeneration, or BvFTD). Admittedly, he lived a long time with the disease, but that’s not totally unusual for those with the behavioral-variant type.

When a parent dies, you learn a lot about them when you go through their things. But one note is incredibly poignant. Even my brother, who I butted heads with when dad had to go into a facility that cost $4,000 per month, now admits what I thought all along: Dad knew this was coming.

There’s no denying it anymore.

“I might have to live in a hospital,” dad wrote in a note explaining his financial decisions. “And at same time banks are not in good shape.”

The date was 1991.

What Happens After the Caregiving Journey Ends

More on…Upon death, ’91 note found: ‘I might have to live in a hospital’…

This is where the sorrow comes in. It’s easy to feel relief over dad’s death, not only because of the horrible physical suffering he endured in the final days of his life, but also because of the suffering my brother and I both endured navigating America’s disgraceful (huge understatement) long-term care system for the elderly.

Dad shelled out $100,000 of his own money to a facility that trespassed me after I complained about an intruder. I complained many times before that about the substandard care he was receiving there, and they made no secret of the fact they didn’t care for my frequent visits. I wasn’t writing dad’s checks, so they had no problem being completely rude every time I brought to their attention something I didn’t like.

And that facility didn’t even send a card to the funeral home when he died, not to mention a plant or flowers.

Disclaimer: There were MANY good people who worked there, particularly before the change in ownership. A few did come to the funeral home.

But in the end, the disgraceful acts of a few created extreme misery not only for my dad, but my entire family.

Not in the very end. I made sure he ended up being moved out of the memory care facility and into a nursing home before he died, and thank God I did, because he died a month later. In the end, he not only ended up “in a hospital,” but the hospital he was born in, which is now a nursing home. They provided wonderful, compassionate care the final month of dad’s life.

Read More: David’s reunion with his dad after 108 days apart, one month prior to Benny’s death

So in the end, after dad spent six figures at this place, we now know that he knew he was going to end up in one of “those places” that all of our parents fear.

And rightly so.

And he made wise financial decisions so that he didn’t go broke in the process. So he could leave something to his children.

But instead of being revered for these selfless acts, he was called “rude, crude, vulgar, inconsiderate and socially unacceptable” for more than 30 years up, by some right up until the day he died. All the while knowing he had a horrible illness and that he was going to end up “living in a hospital” and spending outrageous sums of money. And from my point of view, receiving substandard care for much of that time.

You wouldn’t be hurt if it was your parent?

For now I am seeing a therapist, and trying to work through all of these hurt feelings. I’m not so much angry, but sad. Sad that these places where our parents often lose their life savings can be run by and employ people with apparently no heart at all. I’m sorry, it’s just how I see it.

Again, the first six months in the facility, prior to the regime change, were wonderful. But it sure didn’t end that way.

There is so much to be thankful for and grateful for, and I start each morning giving thanks to God for those things. Above all, I give thanks for my sobriety. For all of the other blessings really mean nothing without that.

A source from a story I wrote for Healthline well over a year ago sent me this Bible verse. It brings tears to my eyes — tears of joy, and tears of healing:

“Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.” – John 12:24.

Wrote the source, “Although Jesus was talking about his death and how it would result in eternal life for many, I think this can relate to your father’s death as well: producing good fruit (your work) for those who are misunderstood, misrepresented, and/or neglected in our society.”

And that brings me great peace.

Making Memories, Not Enemies With Your Loved One With Dementia

You might also like this article: