Senior Moments Are Not Inevitable: 8 Strategies To Prevent Senior Moments with Stan Goldberg PhD

Welcome to Caregiver Relief. I'm Diane Carbo, RN, and today we have a very special guest joining us. Someone who's an incredible career and life experiences are bound to leave a lasting impact on all of us. I am delighted to introduce Dr.

Stan Goldberg, a true luminary in the world of academia and a living example of resilience and compassion. For over 25 years, Dr. Goldberg served as Professor Emeritus in the Department of Speech, Language, and Hearing Services at San Francisco State University. During his tenure, he shared his wealth of knowledge, helping shape the minds of countless students.

But Dr. Goldberg's influence extends far beyond the classroom. He is a very prolific author, having written hundreds of articles and nine books that are in four different languages. And what makes Dr. Goldberg's story even more remarkable is his personal journey. He's a cancer survivor, so he has faced life's most profound challenges head on.

And this experience has fueled his exploration of learning problems, communication disorders, as well as the complexities of loss, change, and end of life issues. But his commitment to making a difference doesn't end there. For eight years, Dr. Goldberg was a dedicated bedside hospice volunteer, providing comfort and solace to those in the most vulnerable moments.

Today, he continues to counsel caregivers, offering his wisdom and support for those who care for others. His extraordinary achievements have not gone unnoticed as Dr. Goldberg has received an astonishing 26 national and international awards, a testament to his dedication and excellence in his field.

Recently, he has become a regular contributor to the esteemed pages of Psychology Today. His debut article, The Seven Most Toxic Myths About Senior Moments, has already garnered significant attention and praise. We are incredibly fortunate to have Dr. Stan Goldberg with us today to delve into the intriguing topic of Senior Moments Are Not Inevitable, and he's going to share eight strategies on how to prevent those senior moments.

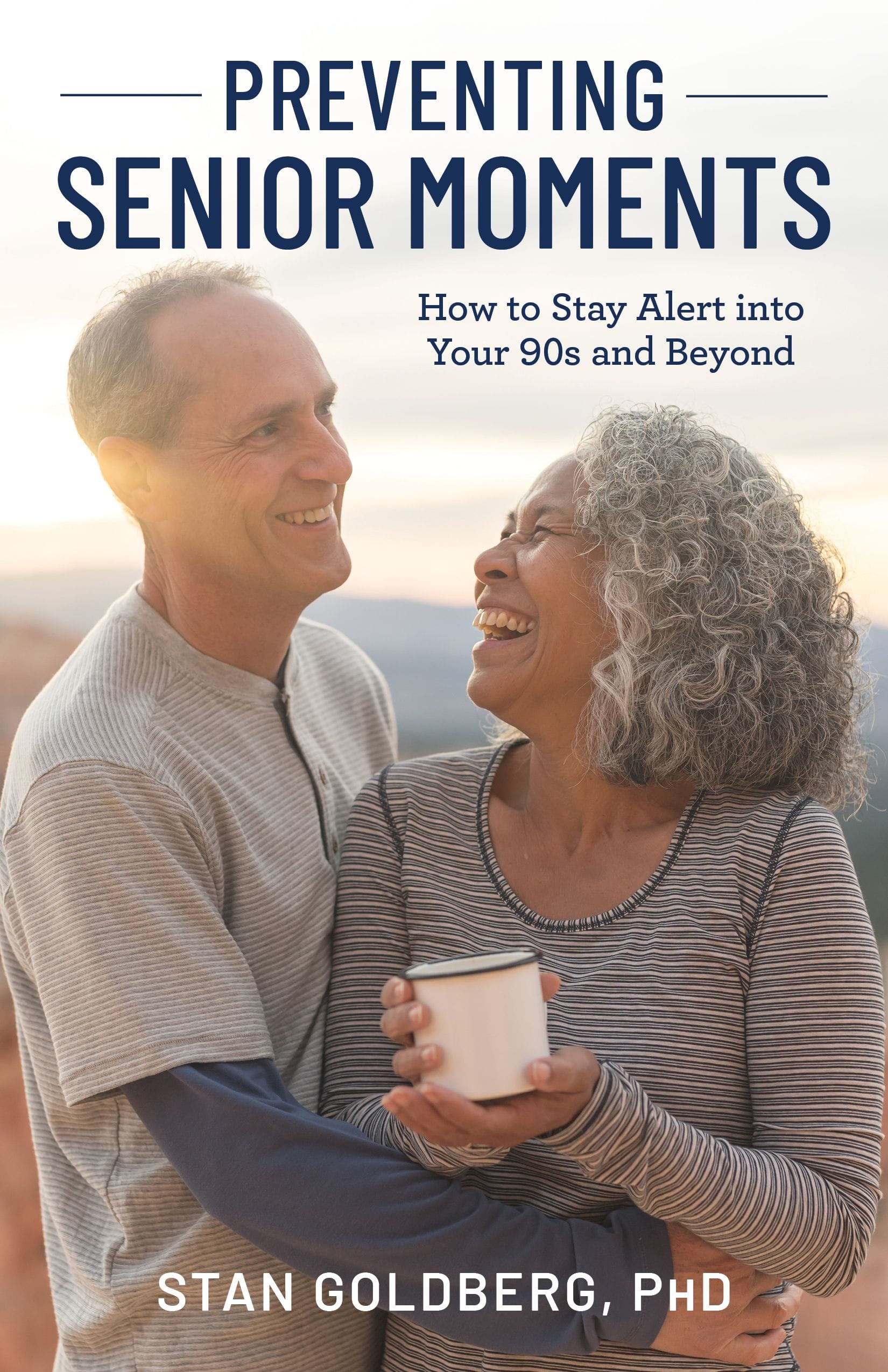

His insights are sure to enlighten and empower us all. And there's more exciting news. Dr. Goldberg's latest book, Preventing Senior Moments, How to Stay Alert into Your 90s and Beyond, has just been released. So today he joins us to discuss this important work and share his insights on staying sharp and focused as we age. So we're incredibly excited.

I'm so fortunate to have Dr. Goldberg carve out some time for us today to delve into the intriguing topic of senior moments that are not inevitable. Stan, I'm so excited to have you here with me today. Welcome. Thank you, Diane. I appreciate being asked. And as I was listening to your introduction, I thought, Who is that person she's talking about?

I'd like to sit down and have a drink with her, but I guess it's me. Oh I'm a big fan of yours, Stan. I followed you for years, and I'm familiar with your writings. And I'm excited about the new book. I'm going to plug it here, Preventing Senior Moments, How to Stay 90s and Belong.

And I want my readers to know that at the bottom of the page that we post this on, there will be a link to purchase your book. Stan, can you explain to me what you mean by senior moment? And then why do you believe they're not inevitable? Yeah, it really started back many years ago when I was visiting a good friend of mine in North Carolina.

And that was the time, I'm not sure it was Haley's comment or was another comment that was circling the earth. And he was trying to explain to me the orbit of the object. And he said this, and I forgot the exact mileage, but he says something like, yeah, that's, it's 13 million miles away from the earth.

And my response was, is that from where we are here or from your house? And I wasn't intending to be funny. But I thought what was going on that led me to the point of making such a ridiculous comment. And I started thinking about. Other comments that I made and other people made and that have been identified as being senior moments.

So I started to look at what people mean by senior moments. So the first thing I did was I did a review of the literature and there was very little, if anything, that was research based and most of The material that I read implied that senior moments were funny, that these are something that you laugh off, you don't take seriously.

They just happen with age. And I started thinking about it and I realized that's not true. And there are more than one type of senior moment. I actually found nine different types of senior moments and we can talk about those shortly. The question then became why do these things happen? And there were so many myths surrounding senior moments that I started to look at each of them, and I realized that there very little was written about senior moments that were, that was factual.

They mostly were myths. And so then I said, okay, why don't I start looking at this? And then I realized it really wasn't sufficient. To investigate senior moments. What I felt was also necessary was to come up with ideas that would help seniors avoid them. Because, for example, the my senior moment about the comment.

That wasn't funny to me, and I've witnessed people, let's say, I've seen a grandmother forget her grandson's name. That wasn't funny to her, nor to her grandson. So the question then became, what can I do to come up with ways in which What we call senior moments are prevented and that's, that was the beginning of the book.

I love it. I'll tell you what, as a woman who's been pre menopausal, post menopausal, and menopausal, I've had word finding problems. And even when I was young, I have, I'm going to share a silly story, but you go down when I yell at the boys. My sons, Jeff and Casey, I would go, Jeff! Casey! But I would start with, Bobby!

Paul! That's my brothers! And then I'd go, Oh, whoever you are, you know who you are! And that was, You're distracted and you think of but I do I have my senior moments where even when I was in my youth, they weren't seeing there we go, senior moments, but they were what you call brain glitches.

Yeah. So the question then becomes, if these aren't things that are inevitable with age, then what are they? Yeah, I started looking at a lot of the primary research on learning, and there was a wonderful article that was virtually ignored, for a long time. This was in 2013, and there was two researchers that were trying to come up with ideas.

That would make it easier for teachers to instill creativity in their students. Wow. So I looked at it and they actually came up with with certain skills that they felt were critical in, in, in order for students to become creative and looked over these and there were six of those. I looked at them.

I said these are pretty much the same as what is involved in cognitive activities. So there's a symmetry between the two. Maybe, I can use this and having a better understanding. Of what we can do to prevent senior moments and what I realized was that if you, these strategies, these skills were also very important in in finding ways in which seniors with dementia could actually grow new neurons and synaptic connections. Wow. And that was different research. So the question then became this seems to be something that can be very important in either preventing dementia or at least, delaying it.

And so that then became one of the strategies, which was essentially you have to keep your mind active. You have to challenge it and you can challenge it through cognitive activities, puzzles. Even coming up with a new recipe. Yeah, it's a cognitive challenge, or you can do it with creativity.

For me, I like playing the flute, and I also sculpt. So for me, I'm getting a lot of a good energy for my brain. Yeah. Thing that I like. So that then became just one of the different strategies, the eight strategies that people can use in order to prevent senior moments. Now, some of these are general strategies, for example.

slowing down. Very few people understand how important slowing down is. Think about your brain and its requirements of doing things in the world as two cogs that need to mesh perfectly. If one of those cogs is slightly out of time, then they're going to clink as they go through, and ergo, you're going to have a senior moment.

So it's a very general strategy, very simple, and especially if people are getting ready for the holiday season, this is something they can do. And so that's just one of the eight strategies. One of the big problems I think we have in our society is, and it's I'm going to, this is going to sound sexist, forgive me, but women do much more multitasking than men do.

And it really, you've got the dishwasher going, you've got the laundry going, you're cooking, you're watching the kids or your adult parent and you don't focus on, you lose your ability to focus on doing one thing well. And I think that multitasking has, is really negatively impacted us as humans.

There's been a lot of research that confirms that. And they looked at the the effectiveness of multitasking to task opposed to a single task. And there's a significant difference. Now, if, that difference gets. Exaggerated as we age, and it does, yeah, multitasking becomes the boogeyman, one of the boogeyman.

Absolutely. We're creating senior moments. Yeah. I love that you encourage creativity. I tell my clients, one of the things you should do is try to do something new and different every day. I don't care if it's taking a different route home or doing something with your non dominant hand or like you said, puzzles.

Games are really good for people to play. I'm not a card person. My whole family loved to play cards. I didn't when I was a kid, I forced myself to do things that I'm unfamiliar with now for that particular reason I need to develop those new neural pathways. So that is something. So can you tell me what are some common misconceptions about memory and cognitive decline and older adults that you aim to debunk.

Yeah. Many people think that all senior moments. Are related to problems in memory. Not true. Most, a lot of them are, but even looking at the ones that are, you need to think about what types of memory, when you look at the research on memory, you end up seeing that there are different types.

Very, the very, at the very simplest level is when you observe something and let's say someone crosses your visual field. Okay. And he has on very bizarre clothing and he has rings coming out of every part of his body, but he walked away. The memory of that is going to stay with you for a very short period of time.

And then following that, then it gets shifted into short term memory and short term memory, there's it's very controversial what really is short term memory. I like the articles that talk about. Short term memory goes from the time it goes from that first type of memory till the time you sleep, and then when you sleep, it becomes long term memory.

So that's a site, there's, that's, we have three types of memory now. A fourth is called sequential memory, and that is the best example is, I'm sitting at my computer, I'm typing, and I want to have a cup of coffee, and I walk up, and I go into the kitchen, and I'm in the kitchen, and I say, Why am I here?

Okay. It's sequential memory. So sometimes, that can cause a senior moment. And so you have these different types of memory that each of them may result in a senior moment, but not necessarily. So you need to, look at what it is. That is causing the senior moment. And usually, it's not necessarily memory, but it's how we process information.

And that's a critical thing. That processing information. What is going on in our brains that takes something we're seeing and in some way manipulates it, stores it, does something with it that somehow gets distorted. And ah, there's your senior moment, the brain glitch, the technical term for it.

I called a brain fart. Now, in your book, you outline strategies to prevent those senior moments. Can you provide an overview of those strategies and their significance? Yeah, I'll go through. There's eight of them and I'll very briefly. Okay, great. Under each of these strategies, there are methods. So the methods are geared to different things.

But the first one I mentioned earlier is to slow down. That's something that is so easy to do and so important in preventing senior moments that, I can't emphasize it hard enough. You slow, you can slow down in your reading. I worked with a woman who would forever would go into her book club meetings and embarrass herself because, what the conclusion she came up with about the book were ridiculous.

So the question became. Should she, she wanted to know, should she just drop out of the group? And I said, no, let's look at what you're doing. So we devised methods of slowing down her reading and doing that resulted in her, making very cogent remarks, at the book club meetings.

So that's the first one. The second one is, is to combat inertia. One of the things that we know about in learning is that if you look at old movies, they tend to be really in confirmed or in your behavioral repertoire, they're solid as concrete. And that's what makes it difficult to change.

So you need to find ways of making these things easier, and you can do that in senior moments as well. Whatever changes that you're going to use in order to stop doing them, they have to be easy, almost as easy as not changing. And this to me is one of the most significant findings is the use of patterns.

If you think about it, the whole world is governed by patterns, whether it's the universe or those termites, that are burrowing in your house. That also do the same thing in South Dakota and Philadelphia, and no one said, hey, this is how you eat up a house, but they figured out how to do that.

So there's a pattern. So patterns are important in two ways. If you know the patterns that are involved in creating a senior moment, you're then in a position to break them. Not only that, but understanding how patterns work. You can create non senior moments by tapping into certain very good example, I used to lose my keys and my wallet constantly, and I needed to figure out what could I do to stop that.

And I figured, okay, I needed to develop a pattern. So the pattern became in my left pocket was my iPhone, in my right pocket, keys and my wallet. And, and I, and that was a pattern that I kept trying to reinforce. And I did that for three months where I would think that constantly. Now that was several years ago.

Okay. If I leave the house and those three objects aren't exactly where they're supposed to be, I panic. I said, something is wrong. Okay. That's of using a pattern to do a behavior. That's not a senior moment. The next one. And we talked about challenging your brain. Something. And it's not it. If you challenge your brain, occasionally, that's like going to the gym once every three weeks.

Do exactly. And for some of my clients, what I had suggested to them, some will do it in terms of they need to do three activities a day. Others wanted to do for certain amount of time a day. And it doesn't make a difference what you choose, but you have to be consistent about that. The next one is make it lasting.

And that's, it has to be concrete. For example, When I, back to my example of the keys before I left the house, this was in the early stages of developing that behavior. I put a giant number three above the door. That said to me, you need to think of three items. So that made it lasting.

So there's different methods that will make things lasting. The next is to focus. We find that quite often if you want to make a behavior lasting and you want to make it endearing, enduring, then what you need to do is you need to focus on it. Some people can do this by meditating before they do an activity.

Others intentionality.

So you have to, be sure that what you're doing is focusing on whatever behavior you want to master. The next is managing your environment, and there's lots of different methods for that. You can create structures, you can impose a structure, you can create different memory stations, and they go on and on.

But basically, the idea is, there are things that in your environment, That you can rely on to help you avoid senior moments. If you find that when you are tired, you tend to get lost more often, then that suggests to you is if I can't sleep more, if I can't do anything about that, then I shouldn't be going into strange neighborhoods.

Yeah. So that's managing. And the last one is practice, which is something that gets ignored quite often. Many people really don't understand how memory works. If you think about doing something from the past, you will find that the more often you had practiced it, the less likely you will forget how to do it.

And what's happening with practice is that it's almost as if new redundant memories I don't know if you, I think one good example is there was a woman that I worked with who often would get lost in new neighborhoods. And, you could first possibly think okay, this might be a sign of dementia or Alzheimer's, but it wasn't. And we needed to do is to think about what is what we could do in order for her not to get so upset about being lost.

So practice being lost, we would go to the outskirts of a new neighborhood and she would go drive a block or 2 and then. Retreat back out again. And we just we keep doing this. So she's now that practicing is laying new layers on that. So after a period of time, she had learned the strategies that she could use to feeling disoriented.

I wish I'd known that when I have a roommate. I did had a roommate, a few years ago that we moved. Here to Myrtle Beach and everywhere we drove, I would make her drive because she was afraid to drive in a strange neighborhood, but I was always out and about and she depended on me to be with her and guide her and I would, we did just that we did short trips to different areas to give her and I, and it's just because she's a very anxious person.

And as soon as she, her anxiety, she gets out of her comfort zone, her anxiety goes sky high and she's, she becomes paralyzed. And I'm sorry, go ahead. No, that's that. And one of the techniques or methods for that is called systematic desensitization, where, if you expose someone enough times to a stimulus that is aversive.

It loses its strength and that becomes a very effective way of reducing or eliminating those types of senior moments. I just, I felt so bad because she'd be driving and we'd be in, it was a street that I had become quickly familiar with. And when I was driving. She was fine but if she had to drive, and that's why I made her drive a lot because I wanted her to learn the new routes.

She would just stop right in the middle of the street and say, do I go right? Do I go left? And I would say, take a deep breath and breathe and think. And we got her to come a little bit more comfortable, but she decided to move back. To Pennsylvania because she just couldn't handle the the new environment.

So I really appreciate you touching on that one. That's a really good one. Thank you. How can maintaining an active social life or engaging in regular social interactions benefit cognitive health and seniors? Okay, let's look at the four skills that are important for either cognitive or creative activities and relate those to.

Why it's important to engage in social activities. So you've got, there's six skills. One, I'll just mention them very briefly, and then we'll talk about it. Providing multiple answers based on available information. The second is this constant analysis of what is being created. The willingness to redraft and start over again.

Thank The fourth is the ability to engage in complex and creative problem solving activities. The fifth is the ability to combine convergent and divergent thinking. And the sixth is willingness to ask what if questions. All those six skills are necessary for social interactions. And I would think that the more you are socially engaged, the more likely it is that these skills are going to be enhanced and developed and the more likely that happens, the greater the possibility that you're going to be creating new neurons and new synaptic connections.

So I, and it's easy. You just, you go out and join a group, you go out and talk to people, have people over for dinner. I think all of those things are important. When I first moved to Myrtle Beach, I'm a retired nurse. With except for the site, and I needed to get out and meet people.

But as you get older, it gets more challenging, once the kids are out of school and stuff. So I started dog sitting because I love animals. And I used to fly, people would fly me, my friends over, Oh, come fly here, stay here. And they'd go on vacation and leave me home with the dogs. But I'll tell you what it has given me.

Number one, because I rent right now. I don't have an ability to have dogs and I like to travel. So having to worry about somebody taking care of my pets is always a challenge worry. So I have the best of both worlds now where I have. Everybody that I are my clients when I dog sit are also my friends and I have, a social interaction, but I also enjoy the benefits of pets that humans don't always give you, and I've seen.

Over my decades of nursing, the benefits of pet therapy to help people because especially those in the early stages of dementia a pet can, they can connect with a pet sometimes better or feel more comfortable connecting with a pet than they do a human because they're afraid they're going to be judged or that they're going to forget something or that makes them uncomfortable.

When I was involved in hospice one of the most enjoyable days the patients had is when the pet therapist would bring the dog up and you would see the, they would just light up the interaction that was with the dog. being created by the pet was really crucial in creating a very peaceful, compassionate setting for the patients.

I had four greyhounds and my oldest grey Kisses was her name. Her track name was Bees Kisses to You. She was the most incredible dog and I took her to the senior centers. And I volunteered at hospice that's hospice is dear to, near and dear to my heart. And we don't utilize it enough, but it's just, it just makes a difference in people's lives.

And it's just, you're right. I love to see them light up when, and it's not because I'm in the room, it's because the. Pat my kisses was there and they would just be so grateful that she was there and they just enjoyed that day and it gave them a sense of calm and the health benefits of having a pet around it lowers your pulse, it lowers your blood pressure and improves your sense of well being.

So it was just a great strategy. And In fact, I'm doing a a series on caregiver robots. And one of the things is people can't have pets all the time anymore. So they've created these creatures, these dogs. One of my favorite is the Parrow seal. I don't know if you're familiar with Parrow. I'm sure you are.

No, it's just. It's a baby seal and it moves and reacts and people just love it. And I saw it in Vegas at a conference, a tech AC it's called CES, it's an international technology conference and it's in Vegas every year. And I went there that it was about 12 years ago, I first saw Perro, and that's when I learned how, and the Japanese developed it.

Because we have that they saw that. The growing aging population, they didn't have enough humans to work with the people that, and we're experiencing that now. So PARO took a took place of something that we humans didn't have time to give, and it made a huge difference. In the care that they were receiving and I like that.

So I really encourage people to and it's hard because today's world loneliness is killing our seniors. It's interesting. I was in Taiwan, probably at least 10 years ago and I was doing a series of lectures on caregiving. And one of the problems that they had was with the reduced birth rate, you didn't have people to take care of their, of the elders anymore.

And it was, it ended up that it was not, it not only affected their physical health, but had a significant impact on their mental health. Exactly. And it was, it, see, thinking about it, now that you brought it up, was I would think that, when you have limited interaction with people all of those skills that are necessary for creative or cognitive activities, they're not there.

. And it's almost like a natural situation for creating senior moments among a population that could at least afford them. Exactly. Absolutely. I always think of my seniors. So many of them are home alone. And that's why even a robotic pet can make a difference. And I just think that we have to look at alternatives to human interaction at a time when we don't have, we're at a I, I call it critical mass crisis right now with the caregivers because we've got the baby boomers coming.

That's why I know this book is going to just be a bestseller because all everybody that's aging needs to know about your preventing senior moments because it's just, it breaks down things easily. And in. Step by step that you can digest what you've learned, and then put it into practice and we need that is as we grow up we have this growing senior population.

Now, you mentioned in your book that physical exercise is a key element in preventing senior moment, could you elaborate on that. Yeah. I think that there's a lot that we know about the brain, and most of which and a lot that we don't know. Thank you. And we know that physical activity in some way affects brain, either physiology or chemical interactions.

We're not quite sure how. I'll give you a very interesting example in Parkinson's. Parkinson's has been studied for a long time. And what recently, They've come up to, to understand that probably the best medicine for Parkinson's, at least early Parkinson's, is physical activity. And they're not quite sure why.

There's different theories on why that happens. But what I think is happening is when you do physical activity, you're taking something that was automatic which is let's say movement, and you're making it very volitional. You're actively engaging or something. I find that physical activity even with people who have less severe problems.

Okay. Is extremely important for preventing senior moments. Very good. Now you also talk about the role a healthy diet plays in preventing memory lapses. Can you talk more about that? Yeah when I was in college and I kept changing the, my major and my mother would have a great deal of difficulty understanding it and even a harder difficulty explaining to her friends.

So when I was working on my doctorate in speech language pathology, I was listening into how she was explaining it to her friends. And she started by saying something about he does things with children's tongues. Okay. And then she said, but you need to understand he's getting a doctorate. But he's not going to be the kind of doctor that helps people.

I would preface that anytime I talk about nutrition. I have a lot of problems with a lot of the claims made in nutrition. There are certain things that in terms of very specific studies. That have been shown to be effective. I have a lot of problems with a lot with the proprietary drugs that you see advertised on television.

I don't know why. That when I buy something. If the advertisement contains any lettering in a font I can't read, something is wrong with the product. Oh, that's a good thing to remember. I think, I think a healthy diet is important. There's a lot of good things that Sanjay Gupta has a book and I forgot the name of it off hand, but he has some very specific recommendations for nutrition.

And in preventing senior moments, I make reference to a lot of those recommendations, but since I'm not the type of doctor that helps people, I'm going to leave those recommendations to others. I just recommend, what's good for the heart is good for the brain. So a heart healthy diet is one that we should all follow.

While I acknowledge that a plant based diet is probably healthy for you and maybe better for you, I'm a person who likes a good steak once in a while. I'll

leave the nutrition recommendations to you. Yeah. And I'm going to recommend that people see a dietician if they really want to learn. Now on stress management is another strategy you highlight. So how can seniors effectively manage stress and what impact does it have on memory and cognitive abilities?

I like to think of stress in terms of muscle recovery. If you think about let's say you go to the gym or exercising your biceps and you're trying to get them stronger, more agile, you're going to be doing things that are very specific for that. And, but you can't, flex your biceps 24 hours a day.

You need at some point to give it a break. The brain works the same way, and I like to think of it as your ability to focus on something is a 10 inch apple pie. And that's it. You can't make your 10 inch pie, 12 inches is a 10 inches. So when you are focusing on something.

Like trying to do things that will prevent senior moments, you have to think about how much energy is my brain using for that. So if let's say you're, you've just you've just finished playing a card game. And your brain is exhausted and let's say it's now down to 50 down to four inches of pie.

I'm now going to start something else that is also very intensive that requires. Eight inches of pie, you're going to have a problem because you're not going to have enough concentration left to do that activity proficiently. When you're thinking in terms of stress, what stress does, it wipes out a lot of your ability to focus.

The question then is, okay, what can I do in order to handle that stress? And when I was doing caregiving, I was counseling caregivers, that was the biggest issue. One of the biggest issue with them was handling stress. Yeah. There's the typical things that everybody hears, you can walk around the block, you can call someone on the phone, you can read a book and anything is fine.

There's no. Specific things that one should do to reduce stress is whatever is beneficial and allows the brain to rest. Okay, that I think is crucial in stress management is some kind of cognitive rest. Yeah, I've never until I read your book. I hadn't known that. Okay, I nobody explained it to me this way and I've been a nurse for 50 years, and I suffer from anxiety at times.

And I know so many of my caregivers, it's funny because when I have my nursing role on, I can handle the world. But, like today, right before our call here. My computer X up. Oh, and my stress level went sky high, thinking, Oh, my God, I got to get on this call. How am I going to do it? The world's going to end.

And I just had to take a step back and say, deep breath, calm down, deep breath, it will work out. And it did. But I had to your I didn't realize that the time. When I was doing it because I've been practicing, calming myself for quite a while now, I'm 70 years old, and I also live with chronic pain, so I feel challenged.

Sometimes to even pay attention to things. If it's a bad pain day for me. The resting the brain makes such. It makes incredible sense to me. And I hope that the caregivers out there listening will take that into under advisement and try to practice resting your brain because we need to move through our lives.

There's lots of different ways of resting the brain. When I was doing hospice. I knew that. From the time I sat with a patient, and our shifts were usually three hour shifts, where I would sit with the patient, I needed to focus as much as I possibly could, because I was about to hear stories and concerns that were so long time ago.

important to the people who I was caring for, that I need to focus. And if I was concerned about a fight I had with my wife, or, my children weren't listening to me, that was going to make it more difficult. So I, I would meditate. Before I saw a patient and meditation is, you could either do sitting meditation.

I prefer to play my flute. So I would find someplace in the corner and I would play my flute for 15 or 20 minutes and that rested my brain. So I think again, there's lots of ways of resting the brain. Each person needs to find out what works for them. Work for them. Yes. Yes. I love that strategy. I I, it's funny because as a nurse, when you put your nurse's hat on and you're going into a unit or, and I've done hospice as well, I just step out of my personal self and become the professional person.

I still joke and tease and have, and still have a life, but I have to always remember that. I had a psychiatrist tell me because I suffer from a treatment resistant depression and I had a psychiatrist tell me you hide your depression very well and it's because I learned early on in my nursing career that you have to turn that side of your life off and focus on providing care for whoever you're with, and it's about them, and not about me.

And I think that we have a hard time in our society right now, separating ourselves, our egos, if you will, from in the professional world and we saw a lot of people will bring drag their baggage with them. And. That's not what any nurse should be doing, they should be focusing on what's important to those around us.

And I learned that early on in my career, and it suited me well because I love to listen, but I also like

to talk. Now, I want I, you're a supporter of Lifelong learning. And could you discuss the significance of lifelong learning and how it contributes to maintaining cognitive sharpness in older adults? Yeah, I think that, there's certain things that are really conducive to keeping your brain sharp.

Something very simple, such as learning a new language. If you think about what's involved in learning a new language, you have all of those those six or seven skills that are involved. You have to do them. If and I run into problems with my friends when I talk about how important video games are.

But video games are really interesting. You can dispute the content, like a lot of violence and narcissism, everything else. But what it's doing, if you can just discount the theme, all of those skills are necessary. In order to play a video game in instead of, banning video games, I was, say, if you can't sit down and play a game of chess or bridge and video games is what turns you on just find one that has a little better content, but it's the actions itself and interesting because it's the actions of most activities that are more important.

Then the goal or the product. So when I'm sculpting and, I'm a very mediocre sculptor, but when I sculpt, I am revitalizing my brain, not by what I'm producing, but the process of actually creating an object. Yeah. And so that, that should be the focus when people are looking at what they can do in order to keep their brain sharp.

Look at the process, forget the product. And I think one of the things seniors have a hard time or as we age, we have a hard time getting out of our comfort zone. I used to try to get friends. I can't sing. I used to play piano. I no longer have the ability. I need to get back to that. But. I try to make myself do things like go out, go to a paint party and be creative doing different things like that.

And I'm shocked at how many people, even at our ages, that are so unwilling because they don't think they're creative. Lord have mercy, develop that part of your brain, have fun with it, but they're so worried about being judged or thinking it's not good enough. And I've gotten to the point, I guess being 70 is very freeing for me because I just say hell I'll just do it.

And if it's not good enough it's good enough for me for now, at least I made the attempt and effort. And for me, it's also about the socialization. I'm the the student in the room that says, Diane, be quiet. What a surprise. But that's okay. It's okay for me. I think if people had that attitude they wouldn't need my book.

The whole notion that you're getting enjoyment and from the process of doing something is I think it's not only critical for preventing senior moments, but I think it's important for getting joy out of life. Exactly. Exactly. I'll give you a perfect example. When I first moved to Myrtle Beach we, I walked the beach every day and I collected shells, all kinds of shells.

Now, Myrtle Beach has a lot of broken shells because of the shoreline, the way it is. So to find a whole shell of any kind. But I was determined the first two years I had collected all these shells and I thought what the heck am I going to do with it. So I decided that I would go to Goodwill and I would buy mirrors, big mirrors, and I would cover them with seashells and sand.

And then I would take them back to Goodwill.

I just wanted the experience. And if somebody appreciated my work, fine. And if they didn't, I didn't spend a lot of money. But I had a lot of fun doing it. And that's really important. And also, I would think of that as taking your brain to the gym. You're going there and you're doing the activities that will strengthen it.

Yeah, I think that. That's how I would like people to think about all of the suggestions in the book, and that is, these are ways, many ways, there's, what, seven or eight strategies and 40 different methods. These are standalone methods that you can use that will not only prevent senior moments, but make your brain a lot healthier than it has been.

I find that doing that now, I haven't done that in a long time with the shells, because it was taking up too much space and I really started focusing more on my site. I miss that creative side to me. And for some women, it could be cooking or baking or whatever you enjoy doing, you should continue to do that for me.

That's cooking is my food of love. And, I get heartbroken when I make things and people don't like them. I'm going, what's wrong with you?

But, I'm my sons were both in Korea and they, I love Korean food. So I tried an Indian food and a lot of people are not open or advantage or adventuresome is the word I want to use when it comes to eating. And I'm like, Get out of my way. Let me try it. If I don't like it, I won't eat it, but I'll at least give it a try.

And I think that people keep themselves from experiencing life because they don't, aren't willing to try something new or different, even a bite of food. Yeah. It's interesting. You mentioned Korea. A number of years ago, I was invited to Korea for the opening of a prostate cancer proton facility.

And One of the most enjoyable things I did was one morning I went out for breakfast and there was nobody there and I found the place that were run by a mother and daughter, a little restaurant. They spoke no English at all. I spoke no Korean at all. And we had to figure out. I had to figure out how I was going to explain to them what I wanted to eat.

They had to figure out how to understand what I was saying. So we eventually did that and they brought this gigantic bowl in front of me. And it contained, although I consider myself a very good Chinese cook I couldn't identify anything. In this bowl, they're completely new. So I had to think about each of these ingredients.

What does this look like? It could I substitute this for something else? Could I find this in the States? And I went on and on. So something even as simple as understanding what you're eating, adds strength. To, to your brain. Exactly. I love experiencing different cultures not just their food but some of their traditions and I just enjoy that so much and we Americans, a lot of times and I don't know how it happens because we have so much diversity in our country but I grew up around food.

The Jews, the Poles, the Italians and it was, and I grew up in the Russian, so I grew up with all kinds of different foods that we incorporated into our daily lives, that then, heck, I remember when pizza became a big thing, and I was at early teens, pizza, and I went to a lot of European films, and I always get a laugh because no matter what country I'm watching the film in, the subtitle film in, there always seems to be pizza in it.

Pizza has become the universal food of the world, next to McDonald's, maybe. Which breaks my heart. Stan, sleep is so underrated, but it plays such a crucial role in cognitive health. Can you explain how getting quality sleep can help prevent senior moments? I wish I could because I can't get quality sleep myself.

I can't anymore either. I think it's, it has a lot to do just with the basic functioning of the brain. If you think about general conditions that make it easier or more difficult to think I can't think of anything more important than quality sleep. Ariana Huffington wrote a great book on sleep on the importance of sleep and what, what you can do.

I've had a sleep disorder since I was in college, which was many years ago. Wow. And it's called a REM sleep disorder. So when you go to bed. And you're having a terrible nightmare, basically paralyzed, you can't, you don't move your arms or anything. You have a REM sleep disorder. You do flail a lot.

Yeah. And that's usually the first indication that you may be prone to Parkinson's. So I've had this for a very long time, and I've been unable to remedy it. By myself. So I've fortunately Stanford Sleep Disorder Clinic is just right down the road for me. It's one of the best in the world. So I've been working with them.

And what I found is by implementing a lot of their suggestions, I'm able to increase both the quantity and quality of my sleep. When I'm able to do that, I'm able to think better. I'm able to yeah. Utilize more of those skills than I can when I've had a poor night's sleep. And actually, I I retired from the university at 57 because of that sleep disorder.

And what happened was I had a my graduate student came in and said, she went there talking about something that happened during my lecture. And I said what was that? And I feared that I had said something terrible. He said the lecture was fine, but it was the same one you gave the previous week, word for word, including the jokes.

And that, that told me it was time to, to retire. But the interesting thing about that was, is how the brain would actually be able to reach back and pull out all of these memories. And actually repeat an experience that I had. So even though that was extreme we do that all the time with even less less severity in our sleep patterns.

And a lot of times that can result and, my clients that resulted in a lot of senior moments where, people went, huh? Why are they saying that without realizing that the cause was poor sleep, which affects the ability to utilize all of these skills that are important for having non senior moment interactions.

I have a lot of clients that and patients over the years that have sleep apnea, they suffer from that, and they don't want to wear the mask or they don't want to do any of those things and it really, you can see their mental health and cognitive abilities decline. There's, I get it. Those masks are horrendous.

And the people now have other options, they have implants or whatever, so they don't have to wear these God awful masks and things, but they really need to learn to address and utilize the benefits of modern technology and get better sleep. One of the things I wanted to address was, how do you identify senior moments that may predict Alzheimer's or other forms of dementia.

So if you look at all of the different types of senior moments. There's only one that stands out that one by itself is more of an indicator of a potential problem than other, and that's disorientation. If you feel disoriented, the well, let me back up a little bit in order not to be disoriented in your brain, there has to be a map.

that tells you where you are and which where you're going. So if I'm, let's say going to Costco, I get in my car, how am I going to get out there? It's not the first time I've been there. It's not even the 20th time I've been there. So my brain now says, okay, he wants to go to Costco.

Okay. How do we go to Costco? It has a map in the brain. And it allows me to drive out there without any problem. And that's normal. We all have rules that we have learned. And we can retrieve them almost instantaneously. But what happens when for whatever reason you can't do it? You can't access it?

That may be an indication that something more serious is going on, other than just a senior moment, but it's not sufficient by itself, which you need to look at are different things that would. Qualify it such as context. What's going on around this disorientation. So here's an example. There was a client I had who was driving to his favorite restaurant, which wasn't more than a few blocks from his house.

And he got lost, totally lost, and which gave him grave concern. So we talked about it. And I wanted to know, tell me what was happening before them. He was wearing a new pair of glasses. He just had a horrendous argument with his wife. He was worried about something in work, and he wasn't quite sure what was going on in his daughter's mind, who he was estranged from.

So that's the context. So what we, I said to him was, okay being disoriented is not something that happened frequently. It's very rare. He said, let's see what happens the next time you are disoriented. By the next week, all of those other issues were resolved and he never had another senior moment involving disorientation.

So that's context. The context will tell you, is this something to be concerned about? The other is severity. How lost, was he getting? Did he just get lost close vicinity? Or did he end up 10 miles away? That would give you more indication as well. The other is frequency.

How often is this happening that can give you an idea of whether this is just the senior moment or this is something on the way to dementia. And the final 1 is the type of problem. If I put my glass, if I lose my glasses constantly in the house, and every time I find them there in a drawer or in a pocket or place, that's 1 thing.

If I put them in the refrigerator. That's different. So whenever making, generalizations about the role of senior moments in predicting dementia, we need to look at all of these factors. And that's something that I think a good neurologist should be able to do. Stan, I'll tell you, I want to plug your book one more time because I think that as a dementia care specialist.

I have a hard time finding a book that speaks clearly and defines what you've done what we, if we face in our brain usually people from academia, forgive me talk about They forget what it's like not to know things, and they talk above people, and you have made this, for me, as a person who's chronic pain, I have a hard time concentrating sometimes.

Again, if I have to do something, it has to be in the morning, because by the afternoon or evening, my mind tires, and I have to have a break. What you've done in this book is break it down into bite sized pieces that are under clearly understandable and it and then

you come up with clear answers. to overcoming those senior moments. So I'm going to recommend everybody get out that wants to prevent dementia and purchase Preventing Senior Moments, How to Stay Alert into Your 90s and Beyond by Dr. Stan Goldberg. P H D, not M D. He's not able to care for people.

And I, I might also add is I have a website, which is stan goldberg writer, W R I T E R dot com. And on that site, I have about 200 articles that are divided into different categories. And you're more than welcome to get on the site and download that. And also There will be a lot of new articles on the Psychology Today website as well.

That's so impressive. I'm so excited. I've been a big fan of yours for many years. I'm excited about this book and a link to your, to purchase your book and a link to your website on Caregiver Relief. Thank you, Diane. I appreciate that. Oh thank you for sharing. I know you your valuable time and carving out a path for us today.

I appreciate that. Thank you.

You can purchase Preventing Senior Moments here

Find Other Books By Stan Goldberg PhD Here

Other articles by Stan Goldberg PhD

You might also like this article: